본문

-

권영우

Untitled, c.1980s Color on Korean paper 51 x 74 cm Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Kukje Gallery Photo: Chunho An Image provided by Kukje Gallery

-

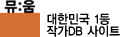

권영우

Untitled, c.1980s Color on Korean paper 47 x 74 cm Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Kukje Gallery Photo: Chunho An Image provided by Kukje Gallery

-

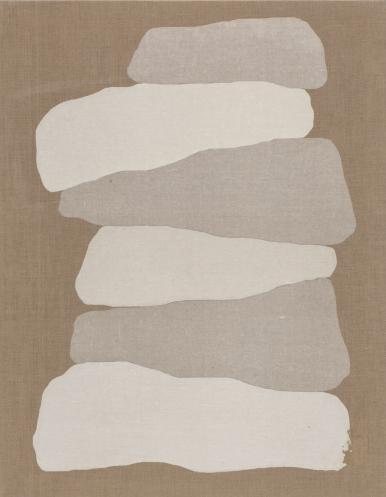

권영우

Untitled, c.2000s Korean paper on canvas 117 x 91 cm Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Kukje Gallery Photo: Chunho An Image provided by Kukje Gallery

-

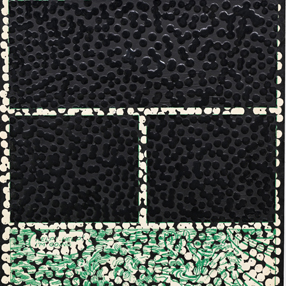

권영우

Untitled, 2002 Korean paper on canvas 130 x 130 cm Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Kukje Gallery Photo: Chunho An Image provided by Kukje Gallery

-

권영우

Untitled, 1982 Korean paper 121 x 94 cm Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Kukje Gallery Photo: Chunho An Image provided by Kukje Gallery

-

권영우

Untitled, c.1980s Korean paper 80 x 67 cm Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Kukje Gallery Image provided by Kukje Gallery

-

Press Release

The creator made everything but did not give a name. Nature itself is an abstraction. I only discover, choose, reform, and add from various phenomena in nature.

– Kwon Young-Woo¹

Kukje Gallery is pleased to announce a solo exhibition of Kwon Young-Woo, a leading artist of the Dansaekhwa movement, on view from December 9, 2021, through January 30, 2022, at the gallery’s K2 space. Marking the artist’s third presentation at the gallery, following solo shows in 2015 and 2017, the exhibition will not only showcase works from the Paris period (1978-1989) defined by Kwon’s iconic work with white hanji (Korean paper), but will also feature for the first time, colored hanji works made upon his return to Korea in 1989. Newer works from the 2000s that incorporate geometric shapes by overlapping hanji on wooden panels will also be shown. The comprehensive span of these distinctive bodies of work allows the exhibition to provide an authoritative overview of Kwon Young-Woo’s practice and the development of his formative language that uses traditional Asian materials in a modern way. It provides a unique opportunity to reflect on the artist’s seminal practice, commitment to traditional aesthetic philosophies, as well as lifelong experimentation and innovation.

As a member of the first generation of artists who came to the fore after Korea’s independence, Kwon Young-Woo was involved in the vital artistic debates that characterized the newly liberated country, where artists argued for and against breaking away from what had been the official Japanese style, and the development of a new ‘national’ art. At the time, Korean art was perceived as having been dominated by Japanese painting, which led towards a concentrated effort to reject this connection and pioneer new methods—a desire that, following the Western model, was founded on the individuality of each artist. Confronted with the shift to post-war abstraction, Kwon—a student of oriental painting—reacted to the search for a new idiom through a unique approach based on modernizing traditional methods. From the outset, he believed it was misguided to distinguish between Western and Eastern painting, saying, “I think it is more meaningful to continue anew than to preserve and inherit tradition.”² In response, he distanced himself from traditional Eastern mediums of the 1960s, such as Chinese ink and the brush, focusing on techniques associated with the selected medium of hanji. Kwon’s works were rooted in Asian tradition, but in line with Western forms—namely post-war abstraction, recalling the ‘papier collé (paper collage)’ by Georges Braque and ‘concetto spaziale (spatial concept)’ of Lucio Fontana. For Kwon, the question of how to compose superseded what to draw, prompting a deep investigation into both the method and meditation on the perception of the picture plane. This formal and conceptual rigor, coupled with the use of Eastern mediums, was the basis of his groundbreaking work which was way ahead of its time.

Kwon began his lifelong practice of experimentation in his earliest works, by exploring the possibility of figurative abstraction with an emphasis on the use of Chinese ink. Around 1962, he started utilizing hanji as a primary sculptural medium. Kwon explained, “My fingers are the most important tool and other various objects are used as tools when necessary.”³ Using his fingertips and handmade tools in lieu of more traditional approaches of drawing on paper, the artist adopted repetitive actions of cutting, tearing, piercing, and pasting, embracing the variability, materiality, and tactility of paper, which lies at the core of his early oeuvre.

Based on his tenacious craftmanship and relentless experimentation, these methods resulted in a breakthrough series during his sojourn in Paris (1978-1989); approximately 18 works from this period are presented on the second floor of K2. These works highlight the delicate texture of hanji arranged in multiple layers, and convey a unique formal language based on the sculptural and rhythmic qualities of the surface. Kwon’s study into the materiality of traditional mediums reveals new narratives that transcend existing boundaries that defined oriental painting.

The first floor of the exhibition presents approximately 11 colored works that Kwon completed shortly after returning to Korea from Paris in 1989, as well as 7 works of layered hanji from the 2000s. This exhibition marks the first time these works in color are shown to the public. While hanji was the artist’s primary medium, Kwon mixed Western gouache and meok (Chinese ink) to add color. Unlike his previous works in which he tried to add spontaneity by tearing and piercing the surface, these paintings are characterized by flat, uniform planes that evoke roller (brush) marks, displaying black, dark brown, and yellow tones created with gouache and meok combined in different ratios.

This balance of different mediums reflects the artist's philosophy on how he does not distinguish between materials from different cultures. Explaining his use of gouache and Chinese ink, Kwon said, “I do not make any distinction between them as others do, and just regard them all as black.”⁴ While Chinese ink smudges and spreads like watercolor, gouache, an opaque water-based pigment, coagulates on its own. Thus, they counteract each other, leaving a lasting impression on the paper. Color, as used by Kwon, is not an additive to the paper, but more of a second surface, existing as a kind of veil. Furthermore, the artist uses the subtle nuances of color, integrating it with the texture of the paper to generate moments of amplified energy, composing space that cannot be bounded.

Kwon, who had repeatedly experimented with three-dimensional paintings by composing around appropriated and found objects in the 1990s, returned to two-dimensional works in the 2000s, continuing his unique exploration of the painting plane. In these more recent works, the artist arranges and reveals geometric shapes through thin layers of hanji on wooden panels. He explores the density of white by applying one or two layers of hwaseonji, a thin and tough type of paper, which is one of the raw materials that create hanji. The more these layers overlap, the more the subtle depth of the paper fiber is revealed—a focus that became the basis of these newer works. Initially inspired by the process of gluing hwaseonji on a drawing board, the resulting layers created elegant yet unexpected dynamics with the paper, that depended on two simple factors: the amount of hwaseonji and glue.

While traditional hanji was his main medium, Kwon consistently used his own hands and handmade tools to study its materiality, employing Chinese ink and color as secondary methods as needed. This focus on the surface was a tenacious and continuous process of realizing the potential of the painting plane, linking his practice to those of modern Western artists. Through the world of abstraction that completely transcended boundaries of the East and the West, Kwon successfully implemented his search for the “connection of the human mind and matter” and reached a “modern return to the origins of the East.”

“조물주는 만물을 만들었지만 이름은 붙이지 않았습니다. 자연 그 자체가 곧 추상인 셈이지요. 저는 단지 자연의 여러 현상들에서 발견하고 선택하고, 이를 다시 고치고 보탤 뿐입니다.” - 권영우¹

국제갤러리는 2021년 12월 9일부터 2022년 1월 30일까지 대표적인 단색화 작가 권영우의 개인전을 K2 공간에서 개최한다. 지난 2015년과 2017년의 개인전에 이어 국제갤러리에서 세 번째로 열리는 이번 전시는 작가의 파리 시기(1978~1989)에 해당하는 백색 한지 작품뿐 아니라, 처음 선보이는 1989년 귀국 직후의 색채 한지 작품, 그리고 패널에 한지를 겹쳐 발라 기하학적 형상을 구현한 2000년대 이후의 작품으로 크게 구성된다. 동양적 재료를 현대적으로 활용하여 새로운 조형언어를 구축한 권영우의 작업 궤적을 아우르는 이번 전시는 그가 단순히 동양화가라는 사실에 머물지 않고 부단한 실험의지로 무장한 동양적인 정신과 기질의 화가로 어떻게 평가받고 있는지를 되짚어 볼 수 있는 소중한 기회를 제공한다.

권영우는 해방 후 1세대에 속하는 작가들 중 하나로, 동시대의 다른 작가들과 함께 해방 공간에서 추구되었던 ‘왜색 탈피’와 ‘민족미술 건설’이라는 시대적 사명에 연루될 수밖에 없었다. 서양화, 조각, 공예 등 다른 미술분야와 비교해 유독 일본화라는 인식이 강했던 동양화 분야에서 일본화풍을 걷어내고 새로운 방법을 모색하려는 노력은 그 어느 때보다도 절박했고, 이는 작가 각자의 개성에 걸맞게 표출되었다. 동양화를 전공한 권영우는 전후 추상의 수용에 직면하여 전통의 현대화라는 맥락에서 당대의 시대적 과업에 응하고자 했다. “전통 문제만 하더라도 이것은 그 자체를 길이 보존하고 계승하는 것보다 새롭게 이어 나가야 하는 것이 진정한 의미라고 생각한다”²고 언급했던 그는, 일찌감치 동양화와 서양화를 구분하는 건 의미 없다고 여겼다. 1960년대 동양화의 주요 재료인 수묵필 중 붓과 먹을 버리고 종이만 취한 그는, 한지를 활용하는 동양화의 기조 위에서 출발하지만 방법 면에서는 조르주 브라크(Georges Braque)의 ‘파피에 콜레(papier collé)’나 루치오 폰타나(Lucio Fontana)의 ‘공간 개념(Concetto spaziale)’ 시리즈를 상기시키는 서구적인 조형방법, 즉 전후 추상미술과 궤를 같이 했다. 권영우에게는 무엇을 그리느냐의 질문 대신, 어떻게 구성해 나갈 것인가의 문제가 전면에 대두되었고, 이 같은 방법론적 탐구와 평면에 대한 투철한 인식은 동양적 재료의 활용과 함께 그의 작품을 시대를 초월하는 현대적인 결과물로 만들어 주었다.

작업 초기 권영우는 한국화의 기본 재료인 수묵으로 필선이 강조된 구상적 추상의 표현 가능성을 탐구하는 작업을 하다가, 1962년을 전후하여 한지를 주요 매체로 적극 사용하기 시작했다. 그는 스스로 “나의 손가락이 가장 중요한 도구이며, 또 다른 여러 가지 물건들이 그때그때 필요에 따라 도구로 동원된다”³고 설명하곤 했다. 그리고는 실제 종이 위에 그림을 그리는 기본적인 행위를 배제한 대신 손톱이나 직접 제작한 도구를 이용하여 종이를 자르고, 찢고, 뚫고, 붙이는 등 물리적이고 직접적인 행위를 통해 우연성이 개입된 작가의 반복적인 행위와 종이의 물질성과 촉각성을 작업의 중심에 놓았다.

어떠한 타협도 불사하는 집요한 장인 정신에 근거한 일련의 종이 작업은 권영우가 프랑스 파리에 체류하던 시기(1978-1989)에 정제된 완성미를 갖추었는데, 본 전시장 2층에서 이 시기의 작품들 위주로 18 점을 선보인다. 이 작품들을 통해 작가는 여러 겹 겹쳐진 한지의 섬세한 재질감을 강조하면서 종이 위에서 입체감과 리듬으로 조형성을 구성하였고, 이는 동양화의 매체를 재조명하여 그 영역을 초월한 새로운 문법이라 평가받고 있다.

국제갤러리에서의 이번 개인전은 앞서 언급한 그간의 다양한 전시들을 통해 선보여온 백색 한지 작업뿐 아니라, 권영우가 파리에서 귀국한 직후 작업한 채색 작품 11점과 2000년대 이후 작업한, 판넬 위에 한지를 겹겹이 붙인 작품 7점을 K2 1층에서 선보인다. 특히 1989년 귀국 직후에 작업한 채색 작품은 이번 전시를 통해 대중에게 처음 선보이는 것들로, 한지 위에 서양의 과슈(gouache)와 동양의 먹을 혼합해 사용함으로써 여전히 종이를 주된 매체로 하되 채색을 화면으로 회귀시켰다. 또한 화면을 찢고 뚫어 화면에 우연성을 가미하고자 했던 이전 시기의 작업과는 달리, 종이 위에 각각 다른 비율로 혼합한 과슈와 먹을 롤러로 민 듯한 평평하고 일률적인 검정색, 암갈색 혹은 노란색의 색면들을 선보였다.

작가는 과슈와 먹의 사용에 대해 “남들은 과슈다, 먹이다 구별을 하는데 나는 그런 구별 자체를 안 하고, 그냥 검정색이다 하고 여긴다”⁴고 언급한 바 있듯, 동·서양의 문화에 기반을 둔 다른 재료들을 딱히 구분 짓지 않았다. 하지만 먹은 번지면서 물기와 함께 확산해 가는 반면 불투명 수성 안료인 과슈는 스스로 응결하기 때문에 서로 역작용 하며, 그로 인해 화면에 은밀한 내재율로 인한 잔잔한 여운을 만들어낸다. 그리하여 권영우가 사용하는 색채는 종이 위에 더해지는 추가물이 아니라 그 자체가 표면이 되어 일종의 베일처럼 존재한다. 더 나아가 색채의 뉘앙스가 종이 표면의 질감과 일체 되어 그 위에 증폭되는 에너지가 작품의 주조를 이루며, 이 에너지는 테두리를 잡을 수 없는 공간 안에 붙들려 있게 된다.

1990년대에 다양한 비미술적 오브제들을 활용해 입체화의 실험을 거듭한 권영우는 2000년대에 들어 나무 판넬 위에 한지를 겹겹이 붙여 기하학적인 형상들을 구현함으로써 평면으로 회귀하는 동시에 회화가 지닌 평면을 지각하는 특유의 작업을 이어갔다. 그는 한지 중에서도 원료에 가장 가까운, 얇고 투명하며 질긴 화선지를 한 장, 두 장 겹쳐 발라 백색의 농도를 표현하였는데, 겹치면 겹칠 수록 한지의 미묘한 깊이가 더 잘 드러났고 이는 곧 작업의 기본이 되었다. 처음 화판에 화선지를 붙여 풀칠하는 과정에서 착안한 이 방법은 중첩의 우연성을 획득하기에 좋은 방식으로 자리잡았고, 이로써 화선지의 수와 바르는 풀의 양을 조절하여 종이에서 일어나는 상황의 생성에 중점을 둘 수 있게 되었다.

권영우는 한지라는 가장 전통적인 재료를 주된 매체로 삼으면서, 오로지 한지 고유의 물성을 실험하고 탐구하기 위해 자신의 손, 스스로 제작하기도 했던 다양한 도구들, 그리고 먹과 안료 등을 부차적으로 활용했다. 그리고 이는 다름 아닌 동시대의 다른 서양화가들도 공히 화두로 삼았던 회화의 평면이 지닌 가능성을 누구보다도 집요하고 부단하게 지각한 과정이었다. 그렇게 동·서양의 한계를 완전히 초극해 당도한 추상의 세계를 통해 권영우는 ‘인간 정신과 물질과의 만남’을 현실화하고, ‘동양 본래의 기원에로의 현대적 회귀’에 도달했다.전시제목권영우 Kwon Young-Woo

전시기간2021.12.09(목) - 2022.01.30(일)

참여작가 권영우

관람시간10:00am - 06:00pm / 일, 휴일 10:00am - 05:00pm

휴관일매주 월요일

장르회화

관람료무료

장소국제갤러리 Kukje Gallery (서울 종로구 소격동 58-1 국제갤러리 K2)

연락처02-733-8449

-

Artists in This Show

-

1926년 함경남도 이원출생

-

국제갤러리(Kukje Gallery) Shows on Mu:umView All

Current Shows

-

네가 4시에 온다면 난 3시부터 행복할 거야

수원시립미술관

2025.04.15 ~ 2026.02.22

-

취향가옥 2: Art in Life, Life in Art 2

디뮤지엄

2025.06.28 ~ 2026.02.22

-

국립아시아문화전당 개관 10주년 기념 특별전시 《봄의 선언》

국립아시아문화전당

2025.09.05 ~ 2026.02.22

-

광복 80주년 기념 «향수(鄕愁), 고향을 그리다»

국립현대미술관

2025.08.14 ~ 2026.02.22

-

이강소_曲水之遊 곡수지유: 실험은 계속된다

대구미술관

2025.09.09 ~ 2026.02.22

-

전국광: 쌓는 친구, 허무는 친구

서울시립 남서울미술관

2025.09.24 ~ 2026.02.22

-

허산옥, 남쪽 창 아래서

전북도립미술관

2025.11.14 ~ 2026.02.22

-

허윤희: 가득찬 빔

대구미술관

2025.11.04 ~ 2026.02.22