김민정: 플로팅 클라우드 Floating Cloud

2023.04.27 ▶ 2023.06.03

2023.04.27 ▶ 2023.06.03

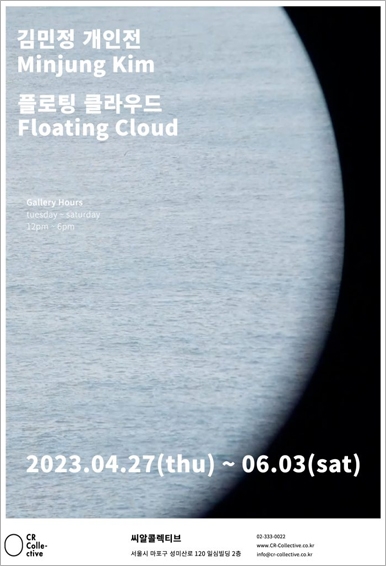

전시 포스터

모든 것은 구름으로부터 시작되었다. 존 더럼 피터스(John Durham Peters)는 그의 저서 『자연과 미디어(원제: The Marvelous Cloud: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media)』에서 자연의 구름과 데이터 클라우드의 구름을 모두 일컫는 중의적 표현을 책의 제목으로 삼았다. 인터넷을 통해 접근할 수 있는 저장 공간은 하필이면 클라우드라는 이름을 갖고 있고, 애플은 iCloud에 디지털로 생산한 데이터를 적재하는 구조를 만들었다. 김민정의 <구름으로부터(From My Cloud)>는 iCloud라는 실체를 감각할 수 없는 무형의 저장소에서 삭제되지 않고 생존한 영상을 모아 엮은 작업이다. 모바일 기기를 사용하는 많은 사람이 생산한 사진과 비디오는 가상의 공간에 부유하는 상태로 쌓여가는데, 김민정도 마찬가지로 지난 10여 년간 촬영하고 실상 쌓아놓기만 하였던 iCloud에 모인, 목적이 없이 단지 “좋아서 찍은” 비 작업용 동영상 소스를 모아 마치 끝말잇기를 하듯 편집하여 작업으로 전환하였다. 용도의 구분을 나누는 것은 일상의 기록/생산물을 ‘동영상’으로 전시나 상영을 위한 작업물을 ‘영상’이라는 용어로 달리 부른다는 지점에서 기인한다. 그러나 실상 영상(映像)은 빛에 의해 맺힌 형상으로 움직이거나 그렇지 않은 모든 이미지를 포괄한다. 그렇다면 본질적으로 접근해 볼 때 우리는 ‘영상’을 무엇으로 인식하고 있는가, ‘영상’과 ‘동영상’의 차이가 왜 존재하는 것인가, 데이터 클라우드에서 유영하던 무빙 이미지를 그러모으는 일로부터 ‘영상’ 작품이 성립할 수 있는가, ‘영상’ 작품이 됨으로써 물신적 가치를 지녀본 적 없는 디지털 무빙 이미지가 물성과 가치를 획득할 수 있는가와 같은 질문을 끌어낼 수 있다. 이러한 의문으로부터 김민정은 ‘영상’이라 불리는 무빙 이미지를 대하는 인식의 차이와 결과물의 위계가 생기는 지점을 짚어본다. 구름(iCloud)으로부터 끌어낸 ‘영상’이 될 수 없었던 ‘동영상’이 경이로운 구름(Marvelous Cloud)이 되어 ‘영상’의 자리에 성공적으로 안착할 수 있을까?

무빙 이미지를 생성하는 매체나 그 결과물이 자리하는 구조의 위계는 여전히 존재하지만, 영상의 제작과 편집에 있어 전문과 비전문의 구분은 사라졌다고 봐도 무방하다. 크리에이트 도구를 사용해 4K로 릴스나 숏츠를 만드는 일이 일상과 같이 이뤄진다. 그 과정에서 음악을 입히고, 필터나 효과를 주어, 텍스트까지 입력해 업로드한다. 한편 아이폰으로 영화를 찍고 시네마틱 모드를 실제 영화 현장에서 촬영 도구로 삼는 일은 더 이상 새삼스럽지도 않다. 핸드폰을 비롯한 모바일 기기가 보편적 매체로 사용됨에 따라 전문 영역으로 국한되는 고사양의 기기나 기법 역시 누구나 접근, 사용할 수 있게 되었다. 4k 마저도 구식이 되어가는 고해상도 이미지가 만연하는 시기에 오히려 저해상도의 이미지는 예스러운 질감과 아날로그적 감수성을 느낄 수 있게 해주는 동시에 현재의 고사양의 모바일 기기에 탑재된 필터와 포스트 프로덕션 효과를 통해 모방하고 싶은 희귀한 원본의 지위를 획득하였다. 김민정은 <일말의 진실(Grain of Truth)>이라는 관용어로부터 이미지를 마치 오래된 과거의 기억과 같이 만드는 효과로 사용되곤 하는 필름 그레인(film grain)을 떠올렸다. 필름을 현상하는 과정에서 빛의 부족으로 화면에 마치 알갱이와 같은 입자가 보이게 되는 이 현상이 적용된 디지털 이미지는 우연성은 삭제되고 인위적으로 시간성을 부여한 조작된 결과물이다. 이처럼 고해상도 이미지를 만드는 매체로 저해상도의 결과를 도출하는 진실의 부재 상태에서 김민정은 뜬구름을 잡듯이 구름 속을 뒤져 조작하지 않은 일말의 진실을 움켜쥘 수 있을지 시도해 본다.

영상 매체를 통과하여 이미지가 그려지는 과정에는 여러 ‘기준’과 ‘표준’에 따라 메겨진 ‘적정’한 값이 필요하다. <사실들(The Facts)>은 홀리스 프램튼(Hollis Frampton)의 <인과응보(Poetic Justice)>와 같은 화면 구성을 취하지만, 테이블에 놓인 타이틀 카드(title card, 영화의 편집을 위해 장면을 설명하는 문장이 담긴 종이) 대신 흰색에서부터 점점 검정에 수렴하는 색의 종이들이 쌓여간다. 그리고 그 양옆으로 적정노출값을 촬영에서 노출과 보정의 기준점이 되는 그레이 카드(gray card)를 두고 찾은 화면(왼쪽)과 카메라에 내장된 반사식 노출계에 의지하여 찾은 화면(오른쪽)이 나란히 있다. 모든 상황을 대표하는 하나의 기준점과 한순간의 정확한 중간 지점은 모두 사실을 사실 그대로 재현하기 위한 근거이지만 서로 상이한 결과를 도출한다. 이에 김민정은 “전체의 밸런스를 위해 대표되는 하나의 기준을 정하는 게 ‘사실’에 근거한 건지, 각자 하나하나의 형편에 맞게 ‘적정’한 상태를 찾는 게 더욱 ‘사실’에 근거한 것인지(작가 노트에서)” 의문을 제기한다. 수증기 덩어리인 구름에 원형이란 원래부터 존재한 적이 없었다. 마치 모습을 바꾸며 떠다니는 구름과 같이 매 순간 변화할 수밖에 없는 ‘기준’과 ‘표준’의 이름으로 작동하는 영상 매체에 있어 절대적 사실과 진실의 상태 역시 존재할 수 없다. 절대적이지 않기에 보이지만 잡을 수 없는 구름처럼 흘러가는 영상을 “경이롭게” 바라볼 수 있을 것이다.

Everything began with the cloud. John Durham Peters employed the term with dual meanings in the title of his book The Marvelous Cloud: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media, referring to both natural clouds and digital data storage. Intriguingly, of all possible names, online data storage has come to be known as “cloud,” and Apple has developed a structure called iCloud, where digitally generated data accumulates within its service. From My Cloud by Minjung Kim is a work created from videos that have survived being deleted in the formless, intangible storage known as iCloud. Photos and videos produced by countless mobile device users continue to accumulate in today’s virtual space, where they simply float around. Over the past ten years, Kim has also amassed video clips in her iCloud that were seized “for the love of it,” without any specific intention. She has combined and edited these clips into a video art piece, editing them together like playing a game of word chain. In Korean, a distinction is made based on their purposes between acasual video clips from everyday life and video footage created for exhibitions or screenings—the former is called “동영상(dongyeongsang, video clips)” and the latter “영상(yeongsang, works of video or moving image).” However, in a strict sense, the Korean word “영상(映像 in Hanja)” is defined as “forms revealed with light” and encompasses all images, whether still or moving. From a fundamental perspective, this distinction raises questions such as: what do we consider to be “영상(video/moving image)”? Why is there a differentiation between “동영상(video clips)” and “영상(video/moving image)”? Can a video art be created by assembling moving images floating within the data cloud then? Can these digital moving images, which have never been assigned any materialistic value, acquire such characteristics and value by becoming a “video art”?

Based on these questions, the artist examines the point at which these moving images, simply referred to as “동영상(video clips),” are perceived differently or where a hierarchy between images emerges. Is it possible for video clips retrieved from iCloud, which might not have been perceived as “영상(video/moving image),” to transform into the “marvelous cloud” and successfully establish themselves as “video works”?

Even though there still is a hierarchy between the media that generate moving images or the structures in which these creations are categorized, it is safe to say that the distinction between professionals and amateurs in creating and editing videos no longer exists. People casually use advanced tools to make 4K “Reels” or “Shorts” videos. They add music, apply filters and effects, and superimpose text, before uploading them. Meanwhile, professional filmmakers are no longer strangers to shooting entire movies on iPhones or utilizing their Cinematic mode in the creation of cinematic works. The widespread adoption of smartphones and other high-spec devices has made techniques and tools traditionally reserved for professionals accessible to all. As high-resolution images become the norm and even 4K starts to feel outdated, low-resolution images have gained status as uncommon originals, providing a vintage texture and an analog feel that many seek to emulate through filters and post-production effects on their cutting-edge mobile devices.

In Grain of Truth (named after the idiom), Kim explores the concept of “film grain,” an effect that imbues an image with a nostalgic air, reminiscent of distant memory. Film grain is in fact a filter that mimics the appearance of grains produced during the development of physical films due to insufficient light. The resulting image is a manipulated product where randomness is removed and a sense of temporality is artificially imposed. In an environment where truth is elusive and low-resolution images are created using high-definition tools, Kim seeks to capture an unmanipulated fragment of truth by “groping through the cloud”—a Korean idiom that, when translated literally, is similar to the English expression “having one’s head in the clouds.”

The process through which image is delivered through video/moving image as a medium requires certain “proper” values determined in accordance with various standards and criteria. Kim’s piece, The Facts, employs the same screen composition as the storied Poetic Justice by Hollis Frampton, but, instead of title cards (used to describe each scene for a film editor), it displays sheets of paper that begin as white and gradually darken, being piled on a table. The video is accompanied by two screens: to the left, there is one where the exposure value is determined using a gray card, a benchmark for shooting and correcting in filmmaking; to the right, there is the other where the exposure value is established using a reflective light meter embedded in the camera. Both a single reference point encompassing all situations and the precise median point calculated for a single moment serve as criteria for the faithful representation of reality, but result in differentiation. By highlighting this distinction, Kim poses a question in her artist’s statement: “Is it more grounded in ‘facts’ to establish a single representative criterion for overall balance or to seek an ‘appropriate’ parameter suited to each circumstance?”

Clouds, being masses of water vapor, never had an archetype in the first place. The workings of the video medium rely on criteria and standards that inevitably shift from moment to moment—like clouds floating in ever-changing forms—thus precluding the possibility of being absolute facts or truth. Instead, we can “marvel” at the images that flow like clouds that are visible yet elusive, as they are not absolute.

전시제목김민정: 플로팅 클라우드 Floating Cloud

전시기간2023.04.27(목) - 2023.06.03(토)

참여작가 김민정

관람시간12:00pm - 06:00pm

휴관일일,월,공휴일 휴관

장르영상

관람료무료

장소씨알콜렉티브 CR Collective (서울 마포구 성미산로 120 (연남동, 일심빌딩) 일심빌딩 2층)

후원단법인 일심, 씨알콜렉티브

연락처02-333-0022

장보윤: 보이스 오버 Voice Over

아트센터예술의시간

2025.11.29 ~ 2026.01.10

이중시선 : MMCA필름앤비디오

국립현대미술관

2025.11.26 ~ 2026.01.10

지역예술도약 《2025 ARKO Leap》

금호미술관

2025.12.12 ~ 2026.01.10

머무르는 순간, 흐르는 마음 Lasting Moments, Floating Heart

수원시립미술관

2025.09.26 ~ 2026.01.11

신세계제과점: 오늘도, 빵과 커피

광주 신세계갤러리

2025.11.28 ~ 2026.01.13

장파 개인전 《Gore Deco》

국제갤러리

2025.12.09 ~ 2026.01.15

다니엘 보이드 개인전 《피네간의 경야》

국제갤러리

2025.12.09 ~ 2026.01.15

아뜰리에 아키 15주년 특별전 《ATELIER AKI: Here and Beyond》 Part II

아뜰리에 아키

2025.12.11 ~ 2026.01.17